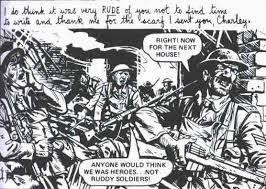

PAT MILLS – JOE

COLQUHOUN – CHARLEY’S WAR – THE GREAT MUTINY

The title may let you think the

subject of the volume is the famous Great Mutiny and you would be totally

mistaken. It only concerns the seven opening episodes. It is an event that only

lasted a few days in September 1917

in the back camp of Etaples. It was started by the Scots

reacting violently at the killing of one of them by the Military Police. The

English, Australians and New Zealanders joined in after a while to free the

prisoners detained in the detention camp waiting for their being shot by a

firing squad. Charley joins this action because a friend of his, Weepers, is in

that “detained situation.” Then they refuse to drill and have a giant sit in. They

were helped in this action by the deserters who are living underground near by

in some cave known as the Sanctuary, led by Blue, essentially.

Apparently that sit-in blocked

all operations in France

on the English side and menaced the planned offensive in Passchendaele. The

main Head Quarters tell the local Officer to yield on the demands of the rank

and file. This leads to going back to business but without the strictest and

most difficult drilling actions and leisure restrictions. Apparently the

prisoners were not recaptured and fired, though Charley helps one to get to the

underground Sanctuary. We have no indication on what happened to the others. In

the mean time an agent of the secret intelligence of the armed forces has

arrived and he has only one objective: to catch the leaders of the mutiny, that

is to say the main leaders of the Sanctuary, the deserters’ camp. That enables

one soldier to give precisions about the way the French repressed a similar

mutiny:

“His

friend Blue told him [Charley]

about the French mutiny. . . it began a few months earlier after the slaughter

of thousands pof French troops in the most horrendous offensive of the war.

Fifty

four French divisions refused to fight. The revolt was ruthlmessly crushed. A battalion

was sent into no man’s land and was massacred by its own artillery.

Decimation was used as a punishment. . . one soldier in ten taken away and shot”

And that is all. In the context

it is obvious the English are being rational and very gentle, considering what

the French did. The point is the English did not do better. But we definitely

lack details. Note along that line this volume publishes in its introduction a French

soldier song of the time attributed to “Paul Vaillant-Couturier, considered the

author of the controversial song ‘La Chanson de Lorette’. A French author,

journalist and politician, he edited the ommunist newspaper L’Humanité in the 1920s.” This is ,a

little short when Wikipedia is a lot more precise: “He was editor in chief of the communist newspaper L'Humanité from April 1926 to September 1929,

then again from May 1934 (officially from July 1935) to his sudden death in 1937.”

When Charley arrives in Sanctuary

with Weepers he finds himself trapped by the arrival of the special intelligence

agent led by a fink who is trying to settle some accounts with Blue because

Blue prevented him, with Charley, from killing one Military Police in the

mutiny. Charley manages to escape because Blue took off and led the “hunting

party” after him. We do not know and are not told what happened to him.

The rest of the volume is

dedicated again to sliced up battlefield experience.

To vary the pleasures and

entertainments, maybe also the points of view, I mean the positions from which

the war is seen, Charley joins the stretcher carriers, a very dangerous

position. His choice is made after Jonesey let himself be blown up by a German

shell because he cannot forgive himself for having been in the firing squad

back in the training camp of Etaples and having shot to death several British

soldiers accused of various crimes with no defense and no appeal. We note here

what I have just said is never said by the author as if he considered military

justice to be an acceptable rule to be played by and respected. Charley wants

to save some lives.

On his team he meets Jack

Masterson who is from the wealthy classes but does not want to speak about it. Once

again the author alludes to the dialect of these upper class people but does

not give the slightest element of it: “Jack sounds

posh. Why isn’t he an officer?” he asks and the answer is: “Something to do with his fmaily. Jack doesn’t

like to talk about it.” We are obliged to imagine what it is to “sound

posh” since we are not provided with an example.

In fact Jack will say a few

things about his motivations: his father is an ammunition industrialist and he

is making a fortune from the war, and he is even selling ammunitions to the

Germans via neutral countries. Jack enlisted as a rank and file and is serving

as a stretcher carrier to save some of the lives his father is killing. Actually

he will identify one shell from his father and that shell will kill him. That

is dramatic for sure but highly improbable. The fact that industrialists made

fortunes out of the war is not the “fault” of these industrialists. It is the fault

of the politicians who decided to have the war and who decided to make it last

as long as possible. And that’s the real shortcoming of the comic strip: it

never really attacks the politicians, the governments, the whatever and whoever

were the real masters of this war. He never goes beyond generals and industrialists,

in other words the technicians and engineers of the war.

[Jack says:] “My father owns the factory that makes them. He’s

a munitions baron. . . a pedlar in death. He’s the only one who’ll get fat out

of this war. Him and the worms.

“

[Charley

says:] Nothing wrong in making a bit pof

a profit, Jack.

[Author’s caption] One famous British arms manufacturer made 34

million pounds profit out of the war.

[Jack says:] No? what about British companies selling war

materials to the Germans through neutral countries?

[Charley says:] I don’t believe that!

[Jack says:] It’s true. That’s why I am stretcher bearer. .

. So I can clear up a little of the mess Dad’s making!”

We can note that more than 75

years after the war, and today one hundred years after it, the author considers

it still taboo to give the name of the industrialist. We can also note the

politicians who authorized the exporting of ammunitions and arms to neutral

countries knowing it was for the Germans are not even alluded to. That’s the

kind of element that completely makes the comic strip fictional if not even

fictitious, and that is regrettable.

At one time a plane crashes in no

man’s land. The pilot is killed but the observer is alive. Charley decides to

save him, Fred Green, and he ends taking him behind the lines to some dressing

station. He has to cross a point known as Hell-Fire Corner that is shelled and

bombed constantly. The two of them are the victims of a close by shell? Fred

Green survives but Charley disappears. We have then an episode in which Fred

Green visits the place where it happened in 1982 and in the course of this

visit he recuperates from his deeper memory the name Charley gave him just

before the explosion: Charley Bourne, and he finds out his name is not on any

memorial or on any list of the victims of the particular battle fought here. But

Fred Green refuses to find out if Charley Bourne is still alive, not to see him

old. Such an episode is trying to build the story as if it were a true story. But

many details are absent that make the story vague and fictitious if not even

dubious. And the reaction of the older Fred Green is unimaginable and in a way

extremely self-centered.

In the same battle the episode

with a German prisoner is strongly anti-German and strongly distasteful. Not

because it is a German soldier who is at stake but because similar episodes

must have occurred daily on all sides of the front and only a German episode of

the type is reported and when something that could be similar on the English

side, though we have not followed any English soldier as a prisoner on the German

side, which reduces us to an English soldier mistreating a German prisoner, it

is presented in such a way that there is an excuse for it. In this present case

there is no excuse whatsoever except – though it’s not mentioned – the fear of

this German soldier being accused of fraternizing with an English soldier by

the Germans who liberated him and took over Charley, and these German soldiers

did not make any prisoners, so why did the German ex-prisoner prevented his

German “colleagues” from dealing with Charley and submitted him to a very

humiliating treatment? Charley’s reaction when the English took over again is

absolutely absurd and inhumane. He is a stretcher carrier and as such is not

supposed to carry or use arms and yet he takes a bayonet and kills the German

ex-prisoner and prisoner again on the spot for the humiliation he submitted him

to, a humiliation that saved Charley’s life.

By the way in 1982, Fred Green is

looking for Charley (whose proper name he cannot yet remember) as being a

member of “a Cockney regiment” but

we have never been given anything like the real cockney dialect.

The episode on the battle of

Cambrai in which an important formation of tanks actually break through the German

lines and come to the very outskirts of Cambrai after an important advance, states

the battle is lost because the cavalry arrives and pretends to have orders from

higher up command not to go after the Germans who are routed. That is in November

1917 when the Russian front has been liberated of its war duties due to the

stepping out of the war by Lenin. You can imagine the reinforcements that are

arriving from the Eastern front

This book comes to a close with

another nasty remarks about officers. The scholar Charley had defended against

a bully a few volumes back has become Charley’s commanding officer. When Charley

finds out on his first meeting with him he exclaims: “Blimey! It’s the scholar! How are you mate?” And the response

of the Scholar turned officer is “I’ll

have none of that ‘mate’ stuff. You’ll forget we were in the ranks together. I

hold his Majesty’s commission. Now it’s ‘Sir’. Understood?”

The author of this comic strip is

systematically trying to force us into believing that the main culprits in that

war were officers and no one else, because they were both socially condescending

and highly incompetent. He even quotes Winston Chruchilm to support his point:

Winston

Churchill wrote that tanks could have stopped the carnage of the trenches. . . “If

only the generals had not been content to fight machine-gun bullets with the

breasts of gallant men, and think that was waging war.”

And Charley is ordered to become

a sniper.

The last box of this volume

introduces us to “the best runner in the

regiment” on the German side, a rare moment when we cross the front

lines, and this runner is “Corporal Adolf

Hitler”. Isn’t that a treat and a coincidence?

This seems to mean that British

generals will never be better than German officers or leaders in the future,

even if they win now, because the German leaders are not coming from the elite

of society but from the rank and file of runners and other dangerous positions

in the war itself. They have experienced courage as a daily counterbalance to

danger and fear in daily missions.

That’s not the case of British

generals, at least in World War One.

Dr Jacques COULARDEAU

# posted by Dr. Jacques COULARDEAU @ 7:26 AM