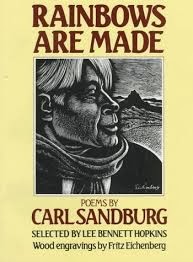

CARL SANDBURG –

CHICAGO POEMS – 1916

Some consider him as the missing

link between Whitman and Ginsberg, but I am afraid this vision is in many ways

warped by considerations that have nothing to do with poetry.

He does not have the

inner-directed and outer-sourced contemplative illumination and sensuousness

that Whitman’s poetry has. For him nature is a far away and abandoned farmland

landscape. For him man’s work is not seen as a muscular and heroic flesh and

blood attractiveness but as a mere uncreative exploitation. The Calamus poems

are just unthinkable within this poetry that is no rocking cradle for anyone,

or actually anything.

He does not have any mystic

humanistic dimension that merges together the humanism of the Renaissance and

the Enlightenment and the mysticism of medieval Christian visionary seers of

the past, present and future within the grail of God’s truth and light, like

T.S. Eliot. God is hardly a pale moon in the sky. No human-mysticism here in

this cold and mute vision of urban life that has lost God and the divine. Such

a world lacks depth and mental soul-like inspiration.

It does not have the rude raw

rough rustic rotten rotting rusted brutal flowing power of Ginsberg that finds

its human force and its beastlike howling in the ruthlessness and awesome total

lack of empathy from a God who has selected his people for them to suffer in

his name for his own glory and for their own misery, their misery being his

pride. There is no howling, yelling, or shouting, not even speaking and

murmuring, not to mention the lack of whispering in this poetry that is mute,

silent, dumb in the meaning of speechless. The last poem is a caricature of

this unspeaking and unspeakable poetry:

“I asked a

gypsy pal

To imitate an

old image . . .

Snatch off the

gag from thy mouth, child,

And be free to

keep silence.

Tell no man

anything for no man listens,

Yet hold thy

lips ready to speak.”

More doomed and desperate than

that you die, but luckily I will survive that pessimism. Man is human in his

ability to communicate and here the poems conclude on the uselessness to say

the slightest little word, not even a cry, a moan, a sigh. Man without communication,

speech and language is nothing but a powerless animal.

He does not even have the

mythological power Crane embodies in his vision of the Brooklyn

Bridge or princess Pocahontas or the Hudson river.

So what does he have if he misses

all that, the underground pulsing blood of the lustful life of nature, the

throbbing heart of the American city, the guilt-ridden recollection of all the

crimes committed in America in the name of some manifest destiny of very bad

repute, the cataclysmic power of the devastating river that is bringing life

through, via, beyond the death it implies when it gets into a furious spree of

“Kill them all, God will retrieve his own!”

Sandburg – by the way the

well-named Sandburg – has a naïve, unelaborated charm of simple images that are

no metaphors, plain emerging revelations of everyday objects or things or

beings, human, vegetal or animal, that-who-which are all silent, wordless,

unspeaking, unable to speak, ghostlike, living dead phantoms of the world and

the cosmos and whose accidental or eventual contributions to the illusive

discourse of humanity will become undecipherable hieroglyphics within one or

two generations. So what the heck! Don’t say a word because it may be used

against you, as Miranda has it, in court or out of court.

The moon is nearly nothing but

the moon, the old moon, dripping, weeping, shedding or pouring her white light

over a world that is hardly alive. Poor evanescent, transient, inconstant

changing moon that is blind to everything and is just forever engulfed in her

successive phases that will never change and never mean anything. Please don’t

swear by it and just forget it. This universe is without any permanence, even

the permanence the poet’s discourse could provide if it were able to look

beyond the surface of things.

A very sad poetry it is because at

first it is the poetry of the big exploitative city, and then the poetry of the

big meaningless war in Europe with its trenches and its mirror-like two

brothers of the shovel and the gun, the shovel that digs the trenches on both

sides, face to face, the gun that kills on both sides, face to face, the shovel

that buries the dead on both sides, face to face, and the gun anew that kills

on both sides, face to face. Yes “the shovel is brother to the gun.” But what a

dehumanized vision!

And dehumanized too the

skyscraper is. Built by anonymous workers, a certain proportion of whom will

die and will be buried within the foundations, the concrete or some forgotten

tombs somewhere else unknown of or ignored by everyone. Thousands of people

will be working or living there and yet that skyscraper has no real life. All

that indeed is nothing but mechanical and heartless agitation. Only at night

some phantasmagorical animation may give that skyscraper some semblance of a

life: “By night the skyscraper looms in the smoke and the stars and has a

soul.” The soul of a bee maybe smoked out of its hive to die along the way

under the stars, probably with the benediction of the moon, that great goddess

of lifeless death.

And the poet is looking for a

refuge in fire, smoke, fog, mist, shadows of all sorts, shade and night. Even

his plowboy and his two horses are lifeless because they are not captured in

their physical muscular fertile effort but only as a shadowy picture against

the sky turning to dusk and night:

“I shall

remember you long,

Plowboy and

horses against the sky in shadow.

I shall

remember you and the picture

You made for

me,

Turning the

turf in the dusk

And haze of an

April gloaming.”

That is really the Twilight of

the Gods, of humanity, of life, of the cosmos even. Where is the life-giving

manly love and brotherhood of Whitman, the rebirth resurrection and renascence

of the mind and the soul of T.S. Eliot, the physical and lustful challenge of

man to society, nature, the universe and the cosmos of Allan Ginsberg?

He only finds a human touch when

he evokes the shadows of humanity that prostitutes are in our urban jungles at

night and in the mist of course. And they are captured as a total absolute

deconstruction of their humanity that was anyway alienated to the service of cows

before and is turned into the alienation of their service of men now.

“Girls fresh

as country wild flowers,

With young

faces tired of the cows and barns. . .

Women of night

life along the shadows,

Lean at your

throats and skulking the walls,

Gaunt as a

bitch worn to the bone,

Under the

paint of your smiling faces:

It is much to be warm and sure of

to-morrow.”

Unluckily there is no to-morrow

really, except oblivion and alienation into non-existence and vanishing.

And that is probably the deeper

meaning of this poetry that emerges from a world that was capturing itself as

having no future, as not being able to have any real objective. The road of

today leads nowhere. It has no end, no destination, nothing but a final point

for each one of us and till then no possible satisfaction of any desire or

wish. The Sphinx as he says is silent, mute and has nothing to tell us. He, the

poet, is nothing but the copper wire on a telephone pole.

“I am a copper

wire slung in the air. . .

Death and

laughter of men and women passing through me, carrier of your speech,

In the rain

and the wet dripping, in the dawn and the shine drying,

A copper wire.”

And the poet has little say

except that he has little to say:

“Your song

dies and changes

And is not

here to-morrow

Any more than

the wind

Blowing ten

thousand years ago.”

That poetry then speaks because

it is silent. The poet makes sense because he is senseless and meaningless. But

he sure is all by himself, apart from everyone and standing alone. Even more

alone than Emily Dickinson lost in her father-dominated spinsterhood and

reclusion. As he says he deserves to be crucified but with silver nails because

it is a once-in-a-lifetime event, the crucifixion I mean, not the poet himself.

“Every man is crucified only once in his life and the law of humanity dictates

silver nails be used for the job.” And silver nails it will be, for the sake of

tradition, from yesterday to tomorrow and everyday in-between those two.

And some pretend that he was a

militant of the progressive if not revolutionary working class avant-garde

fighting for . . . socialism. . . what’s that by the way?

Dr Jacques COULARDEAU

# posted by Dr. Jacques COULARDEAU @ 9:44 AM